Great Sagebrush Sparrow Hunt

Nov 2020 to

Feb 2021

Nov 2020 to Feb 2021

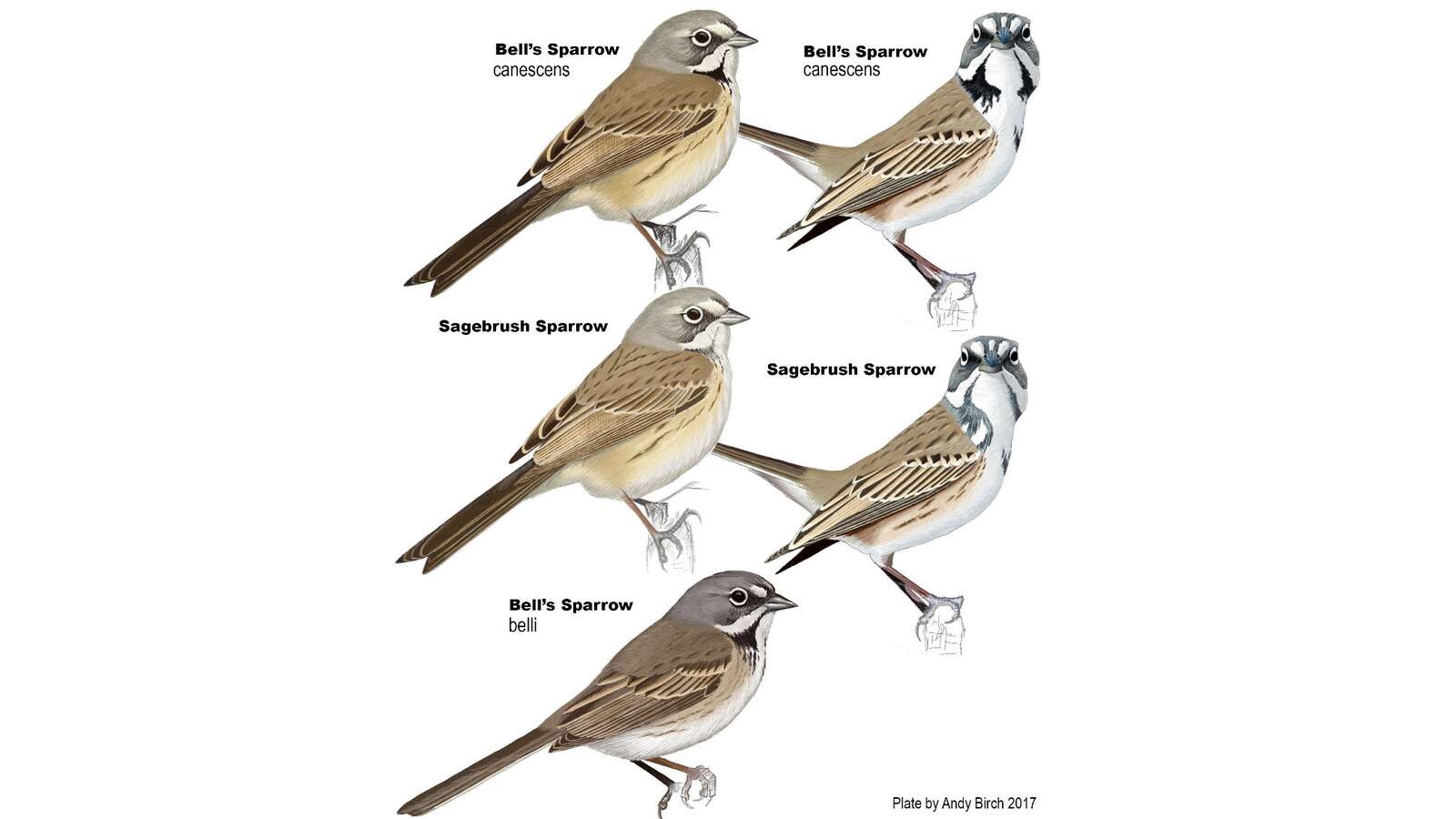

Sagebrush Sparrow, Artemisiospiza nevadensis, is a Great Basin species recently split from what was formerly called Sage Sparrow. It is challenging to distinguish Sagebrush Sparrow from the interior subspecies of Bell’s Sparrow, Artemisiospiza belli canescens, and therefore the wintering range of Sagebrush Sparrow is not well understood, particularly in Los Angeles County where Sagebrush Sparrow is suspected to occur.

The Great Sagebrush Sparrow Hunt is an effort to document the occurrence of Sagebrush Sparrows, in Los Angeles County.

The status, distribution, and identification of “Sage” sparrows are discussed at length in this webinar. Protocols for this project, and updates on its progress, are listed below.

Protocols for the Great Sagebrush Sparrow Hunt

WHEN: Based on what we know about breeding, migration and molt in the Sagebrush Sparrow, it appears that late fall and winter is the best time to search for them in Los Angeles County. So try hunting between now (mid-November) and February.

WHEN: Based on what we know about breeding, migration and molt in the Sagebrush Sparrow, it appears that late fall and winter is the best time to search for them in Los Angeles County. So try hunting between now (mid-November) and February.

WHERE: The two specimens of Sagebrush Sparrow at the L. A. County Museum from Los Angeles County are from the coastal slope (San Fernando) and islands (San Clemente I.); any “Sage Sparrow” in the coastal lowlands or islands (apart from the resident population of Bell’s on San Clemente) is most likely going to prove to be a Sagebrush. But such records are very few.

However, arid scrub in the desert portion of the county is the most likely place to find them – roughly coinciding with the year-round range of canescens Bell’s Sparrows.

Searching should be concentrated on flat or gently sloping desert habitats dominated by creosote or by saltbush. Much of the eastern Antelope Valley north of Hwy 138 consists of such habitat, along with portions of the western Antelope Valley roughly north of Ave J. “Sage sparrows” often also concentrate around the perimeter of parks and wetlands where some water is available (e.g. Apollo Park, Piute Ponds, Rancho Sierra Golf Club, Sorensen Park, etc.); however, those areas already receive frequent coverage, so it is best to concentrate on other, poorly-birded sites.

CHOOSING AN AREA OR ROUTE: The far eastern and northeastern portions of the county are rarely covered by birders, and most of the Sagebrush Sparrow hunt should be concentrated there.

Choose one or more roadside routes of 2 to 3 miles (in any case, no more than 5 miles) each – by scanning and walking you should be able to cover about ¼ mile (or more) on either side of the road.

RECORDING DATA: Each area or route will be entered as one eBird list. In the Checklist Comments section, indicate “Great Sagebrush Sparrow Hunt”, record weather conditions, and provide a summary of the habitat(s) covered – e.g. creosote scrub; alluvial wash with saltbush; scattered Joshua tree woodland; rocky butte, abandoned agricultural fields; etc. Enter all bird species encountered with numbers. It is important to enter eBird lists even if no Bell’s or Sagebrush Sparrows were encountered.

SEARCHING TECHNIQUES: A spotting scope is essential as “sage sparrows” will often tee up at a distance and not approach closely. Consider using song playback (many Sagebrush and canescens Bell’s Sparrow song recordings are available on Xeno-canto and elsewhere). “Sage sparrows” don’t sing spontaneously much in winter, but may respond to tapes by approaching. Have your camera with telephoto lens ready, as photo-documentation of suspected Sagebrush Sparrows will be critically important.

You will probably encounter canescens Bell’s Sparrows, possibly even in large numbers. There is some indication from studies in southwestern Arizona that the two species stay generally separate, but that may not necessarily be the case here. Obviously all “sage sparrows” should be examined as carefully as possible.

DOCUMENTATION: The ideal documentation will consist of sharp photos showing the entire back and also the head/malar region, along with written notes about key ID characters. This is a tall order, but try to get as many photos of suspected Sagebrush Sparrows as possible. If a bird is singing, please try to get audio recordings (even with your cellphone), since the song of canescens is distinguishable from the song of Sagebrush. The call notes are not known to differ.

OTHER NOTES AND CAUTIONS: Search parties should consist of household members only in a single vehicle, as COVID protocols will obviously need to be followed. However, two or more parties in separate vehicles can team up as long as all COVID precautions are followed when the parties are together in the field.

Very strong winds will make searching difficult or impossible, so try to aim for days when strong winds are not predicted (a few such days do exist in the Antelope Valley, believe it or not).

SIGNING UP: There is no need to formally sign up to conduct a search. But it would be helpful if you let Kimball Garrett (the “compiler”) know what areas you planned to cover so other groups can be deployed to maximize the total area of coverage. Also, feel free to contact the compiler if you have questions about searching or about what you found.

Kimball Garrett can be contacted at kgarreiottt@nhm.org.

Update on the Great Sagebrush Sparrow Hunt

January 10, 2021

We are very encouraged with the initial field efforts in late November and December – several birds with plumage matching that expected for Sagebrush Sparrow were induced to sing through playback and gave what appear to be diagnostic Sagebrush Sparrow songs. So we know they are out there, and possibly not even rare (but do bear in mind that Bell’s Sparrows of the subspecies canescens are far more numerous and widespread).

Having said that, it is clear that this is a difficult, if not intractable, field identification issue. We know that canescens Bell’s Sparrows can show some streaking across the entire back as well as great variation in the width and extent of the black malar. So we are still trying to refine exactly what the diagnostic characters are (besides species-specific songs). Some frustrated observers have called into question the validity of Sagebrush Sparrow as a species distinct from Bell’s Sparrow (i.e., The Great Sagebrush Sparrow Hoax”). But bear in mind that species are not defined by the ability of birders to identify them but rather by biological attributes determined from specimens and from intensive field studies (e.g., morphology, genetics, ecology, behavior, and extent of interbreeding). Bell’s and Sagebrush Sparrows “act” like good species where their breeding ranges meet in northern Inyo County, CA.

So we urge all of you to spend time in the Antelope Valley looking through “Sage” Sparrows from now into March. It is our assumption, though unproven, that Sagebrush Sparrows will be more likely to sing in response to playback (and maybe even spontaneously) as hormone titers ramp up with the approaching spring migration and breeding season. Some observers have already (early January) noticed an uptick in spontaneous singing of Bell’s Sparrows, though that is more expected since they breed commonly in the Antelope Valley.

Most of the probable Sagebrush Sparrows have been east of Lancaster and north and east of Lake Los Angeles, but very similar creosote or mixed shrub habitat occurs south to the northern flank of the San Gabriel Mtns. (up to about 2500-3000’ elevation) and in scattered pockets in much of the western Antelope Valley north of Hwy 138. Any and all of these areas should be searched, but we don’t have enough knowledge yet to suggest specific habitat conditions. Don’t worry if areas you choose to search have already been covered – as composition of sparrow flocks at a given site seems to vary from week to week if not day to day.

The following seems to be the best strategy:

-

Find a paved or passable dirt road that traverses creosote and/or Atriplex scrub habitat. Try to avoid busy highways, and always be careful on dirt roads for sandy patches and especially for trash in the road that might contain sharp objects [every dirt road in the Antelope Valley is an unofficial and illegal dumping site.]

-

Stop and wander into scrub away from the road, pishing or using song playback to attract sparrows. A spotting scope is essential to see plumage details of birds as they (ideally) tee up atop a shrub.

-

You may have to stay with a bird a while to see and photograph its dorsal surface (the key area, along with the head/malar region).

-

If the bird is spontaneously singing or responds to playback, try to get a recording. (See below for more details on getting recordings). Note that Bell’s Sparrows will often respond by singing to Sagebrush Sparrow playback, but a Sagebrush Sparrow should as well. So far the only sightings we are inclined to accept as Sagebrush Sparrows involve well-photographed birds that were also song-recorded. So if you get a Sagebrush candidate, spend as much time as you can with it for photos and recordings.

-

Good numbers of sparrows (and other birds) are attracted to small puddles and water drips – a few of these occur out in the Antelope Valley. This is a good way to examine a lot of birds, but less than ideal for getting song recordings.

We encourage everyone who hears Bell’s Sparrows and Sagebrush Sparrow candidates to record their calls and songs. Although we welcome recordings obtained with dedicated recording equipment, recordings obtained with cell phones are also ideal to contribute to this effort.

Most cell phones come equipped with at least one app that allows users to make recordings. In general, recordings obtained with these apps (such as “Voice Memo” on iPhones) are in the compressed m4a format that is fine for documenting birds. For a few dollars, though, we recommend installing apps such as Voice Record Pro, Rode Rec, Rec Forge (for Android phones) and others on your phone that allow you to record “wav” files that are uncompressed and thus contain more information with each recording.

Once you have a recording, what should you do with it? Arguably the most important thing is to add your recordings to your eBird lists to document what you found, share the results with everyone, and so your contributions will be archived with the Macaulay Library at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. Sound files uploaded to eBird lists will make lasting contributions whose value will increase with time; they are directly analogous to museum specimens.

To upload your sound files, you first need to get the recording from your phone to a computer and then add it to the eBird list. The method to transfer the sound files from the phone to the computer varies with the phone app, but most allow you to use the email app on the phone to email the file to yourself (then you can then retrieve the sound file from email on a computer); transfer the file to Google Drive, Dropbox, and then get it to a computer; use AirDrop (on an iPhone); and so forth. Transfer of the sound files from a phone to a computer generally does not require any sort of cable to connect the devices. When you have the file on your computer, upload it to your eBird list using the “Manage Media” option that you use to add photos to an eBird list.

To the best of our knowledge, it’s not possible (yet) to transfer sound files from a phone directly to an eBird list, but if someone knows otherwise, please let us know.

If you’re not familiar with editing sound files, don’t worry about it, and please upload your files as they are. If you’ve had some sound editing experience, eBird welcomes files with minor edits such as removing handling noise at the beginning and end of the file, and normalizing the volume to -3 dB, but otherwise eBird prefers that sound files have no other edits (for example, no high- or low-pass filtering, even if there’s a lot of background noise). Again, if you’re not familiar with how to edit sound files, don’t worry about this.

eBird allows you to upload files in “wav,” “mp3,” and “m4a” formats, which are the most widely used sound file formats currently in use.

Thanks for helping out with this effort, and best of luck in the field.

Kimball Garrett and Lance Benner

LABirders Science and Research Committee